Ugh. I does sometimes feel like this blog is just a means for me to moan. But taking a step back, and looking at the several (or more) years that I’ve been writing on here, I also feel that it’s reasonable for it to reflect my state of mind at any given time. Sometimes, that state of mind is influenced by personal stuff (no, the kitchen still isn’t finished and they’ve also managed to not connect the sink up correctly, so they’ve destroyed some cupboards as well), sometimes by life in general. Probably most often both, with some delicious interplay between the two.

But the last couple of months have been… bad.

- Two tigers on the loose

- One lion on the loose

- The attempted cyanide poisoning of the head of the country’s electricity utility

- Aforementioned head laying bare the corruption within that organisation

- Apparent assassination of a popular musician

- Worsening rolling blackouts

- Wargames with the bad boys

- General kakistocracy and kleptocracy (see 6000 miles… passim)

Are things going to get any better? Well, hopefully, yes. But perhaps not just yet.

We have a few things to deal with before that:

- A genuine potential for WW3

- Potential grid collapse in SA

As an aside: warnings of both of the above have been circulating for years now, but were often just seen as just media scaremongering. Right now – sadly – they both seem entirely plausible. - Justified(?) US/Western sanctions against South Africa

- Entirely preventable Measles outbreaks

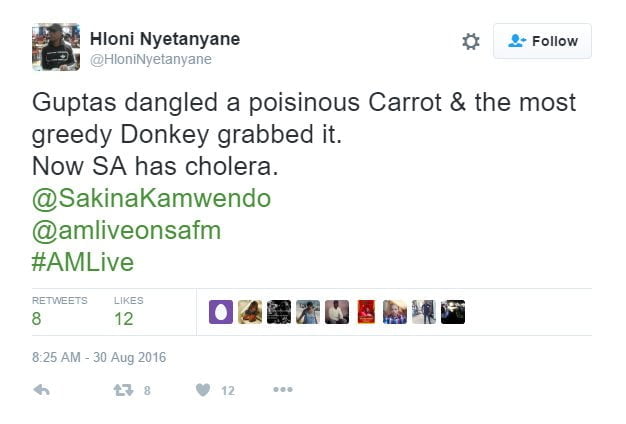

- Incoming cholera

It’s a lot.

The light at the end of the tunnel?

I want to believe it’s there, but I just can’t see it at the moment.